Over the decades, the label “Mexican Style” in boxing has become synonymous with all-out attacks at the expense of defense, a badge of honor and a promise of fireworks in the ring — all rolled into one.

So as Canelo Alvarez seeks to unify the super middleweight titles Saturday against Billy Joe Saunders in Arlington, Texas, boxing’s biggest draw will continue to rely on a formula that has helped him climb to the top of the pound-for-pound rankings and stake his claim among Mexico’s long list of great champions. His unique brand of Mexican Style, a more — dare we say — defensive approach, has kept him fresh and successful after 16 years as a pro.

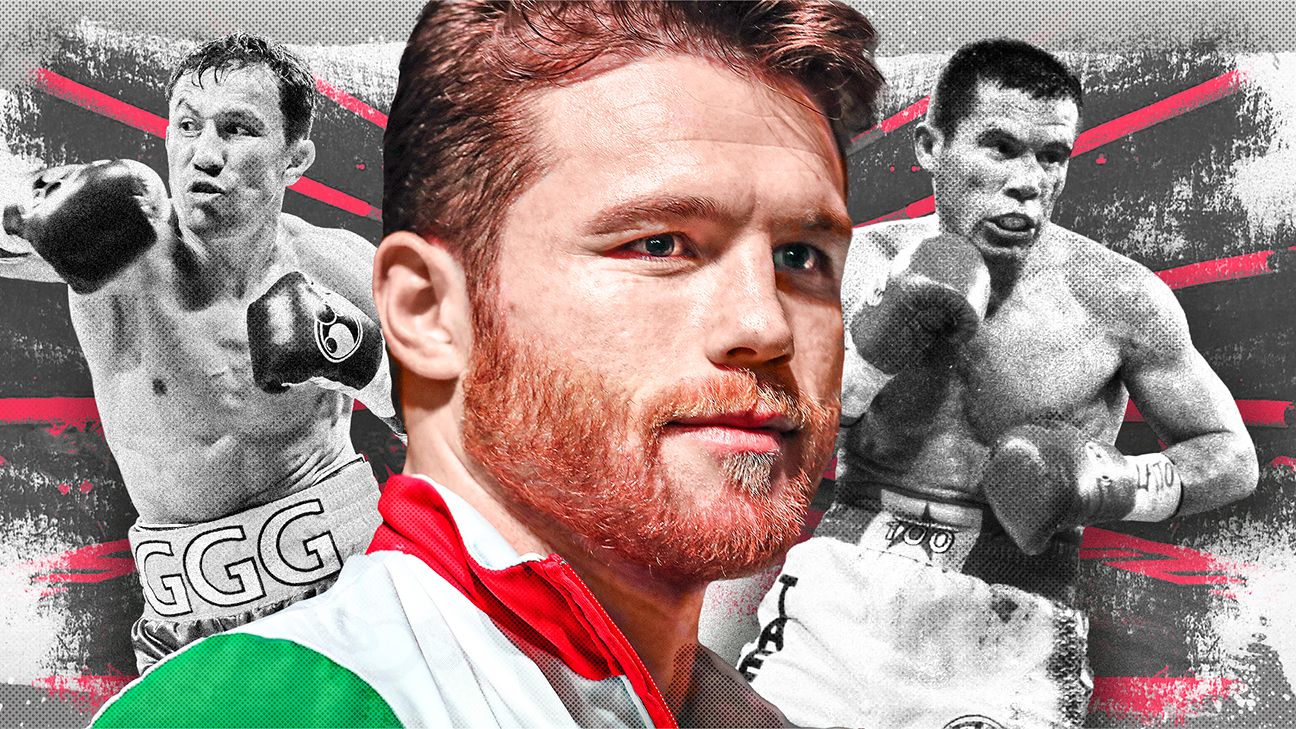

Since enduring his only loss as a pro to Floyd Mayweather Jr. in September 2013, Alvarez’s knockout rate has dipped to 43% with just six in 14 bouts — an understandable development considering the higher level of opposition he’s faced. With the possible exception of his fights against Gennady Golovkin, it’s difficult to argue Alvarez has ever looked out of command or been in serious trouble in the ring.

0:42

The WBC and WBA super middleweight champion who fights Billy Joe Saunders on Saturday says that Mexican Style boxing is not just about getting knocked down and getting back up.

“Mexican Style isn’t taking punches and getting knocked down for the sake of it,” Alvarez told ESPN last month. “Mexican boxers know how to move, how to not get hit — it’s boxing in and of itself.”

Though Mexican Style long ago evolved to include fighters of all weights and nationalities, personal traits — courage, heart and endurance are popular descriptors — remain key when nailing down what it is exactly and whether Alvarez embodies it.

One thing is clear: Because of his massive success and appeal over the past decade, Alvarez (55-1-2, 37 KOs) has set himself apart as a must-see headliner. His two middleweight bouts against Golovkin generated a combined 2.4 million pay-per-view buys, with the second affair earning at least $94 million in domestic television sales.

Oddly, the ever-evolving definition of Mexican Style took a twist as Alvarez prepared for those two bouts against the Kazakhstani fighter. Abel Sanchez, who molded the power-punching Golovkin toward an approach more reminiscent of pressure boxers such as multiple-time world champion Julio Cesar Chavez, argued that his fighter, and not Alvarez, was the modern archetype of Mexican Style. In his prime, Chavez — the quintessential Mexican legend — wore opponents down with speedy, relentless barrages targeting the body, often with little regard for defense.

In 2018, a year after their first meeting ended in a draw, Alvarez emerged victorious in a September rematch against Golovkin via controversial split decision. Golovkin got his wish to force Alvarez into a less defensive stance in a bout subsequently voted Fight of the Year by The Ring magazine, but it was Alvarez who on that night became the sport’s most bankable star.

“Look, Mexican Style is counterpunching. Scoring combinations and finishing with hooks,” said Eddy Reynoso, Alvarez’s trainer. “You have to be technical. I believe the Mexican school of boxing is the most complete out there because it teaches you defensive tactics and offensive tactics.

“Those who say the Mexican school is all about punching and attacking, that’s not Mexican Style. That’s the Mexican race, always willing to die on the line.”

Lessons learned

In breaking down Alvarez, Reynoso checked off all the boxes. He describes his boxer as high class, a good counterpuncher who is smart in the ring. A fighter who works his jab to his advantage, knows how to feint and how to use the ropes. Knows when to step forward and when to retreat.

All these traits, Reynoso said, developed from years of tinkering his style and learning from the best Mexico has to offer — studying video of champions such as Jose Medel, Gilberto Roman, Jose “Mantequilla” Napoles and Chavez himself.

“As Mexicans, we’ll always have a cloth from which to cut because we have a history of over 150 champions from our country we can study, and each one of them has specific qualities,” Reynoso said. “There are boxers like Saul [Alvarez’s given name] who are quick studies, and the results show it. He’s a complete fighter.”

Still, there was a learning curve. Earlier in his career, offensive displays were Alvarez’s calling card.

Alvarez came into his light middleweight fight against Mayweather having knocked out 30 of his 43 opponents. That was in stark contrast to Mayweather, who had scored just five knockouts in the previous decade leading up to their meeting.

On the night, Alvarez fulfilled his role as the aggressor, but Mayweather consistently denied him solid contact. The more experienced Mayweather thoroughly outperformed a then 23-year-old Alvarez, landing 115 more punches despite attempting 21 fewer shots.

Judges awarded Mayweather a majority decision, as CompuBox numbers showed Alvarez landed just 22% of his punches.

The defeat was undoubtedly a turning point in Alvarez’s career.

“I’ve matured so much since then,” Alvarez said on Hotboxin’, Mike Tyson’s podcast. “I needed more experience, more maturity. I don’t take that fight as a loss; I take it as a lesson. I learned from that fight.”

Before his enlightenment, it could be argued Alvarez’s approach to Mexican Style boiled down — as it did with many of its disciples — to a single, time-tested slang word in Spanish referencing manhood:

“Huevos,” said Roberto Andrade Franco, who has covered themes surrounding Mexican Style for various publications. “It’s the heart of a champion, getting back up figuratively and literally when things get tough.”

Chavez’s rise in the 1980’s exemplified this approach and took hold of the sport beyond Mexico’s borders. His penchant for delivering electrifying knockouts and dominating fighters across several weight classes with a signature combination of punishing body blows and sharp uppercuts punctuated “el estilo mexicano.” In doing so, Chavez unified separate elements his predecessors had exhibited into one superstar boxer.

Tactically, Mexican Style can perhaps best be described as a mix between the aggressive, pressure styles of a swarmer such as Chavez and the speed, technique and power required of a boxer-puncher.

“I think there are many styles within Mexican boxing,” Alvarez said. “It’s not necessarily going in to hit your opponent while he hits you. Getting knocked down and getting up.”

Reynoso’s description of Mexican Style — counterpunching, combinations, hooks — brings to mind an exciting puncher capable of scoring explosive results, but also the surgical, disciplined boxer who dismantles opponents methodically while avoiding danger.

“Every fighter you face is different,” Andy Ruiz, the former heavyweight champion of Mexican heritage who is also trained by Reynoso, told ESPN before his win over Chris Arreola last Saturday night. “You have to fight everyone differently. Even if you have a specific style, sometimes you have to perfect other skills [to win.]”

Sustainability concerns

For all its entertainment value and effectiveness, the sustainability of Mexican Style is questionable, more than anything because of the toll it can take. Chavez, the poster boy for Mexican Style, also serves as a warning of its effects.

At 31, Alvarez is still in his prime despite logging almost 60 bouts in more than a decade and a half as a professional. Chavez received the first blemish to an otherwise perfect record at the same age with his controversial draw against Pernell Whittaker in 1993.

1:13

Reynoso says the Guadalajara native has drawn from other Mexican greats to create his own brand of Mexican Style boxing.

Just four months later, Chavez lost to Frankie Randall and looked significantly slower. He had complained of problems with his arms and knees, as years of intense showdowns against opponents such as Meldrick Taylor and Edwin Rosario — bouts that Andrade Franco considers textbook lessons in Mexican Style — had taxed him significantly.

Before taking on Oscar De La Hoya in 1996, Chavez admitted the bout against the U.S. Olympic gold medalist of Mexican descent was financially motivated. The much younger De La Hoya, who would later become Alvarez’s promoter at Golden Boy, won in the fourth round when the ringside physician stopped a bloodied Chavez from continuing. De La Hoya had landed 94 punches, while in comparison Chavez attempted just 85.

Chavez dragged on for nearly another decade after his first meeting with De La Hoya, losing four more times in the process before finishing with a career mark of 107-6-2. It was a knee-buckling uppercut in the late rounds to the legacy of El Gran Campeón Mexicano, who has also admitted to battling substance abuse problems in the latter part of his career.

“Canelo’s smart,” Andrade Franco said. “He could probably box for another 10 years the way he’s doing it. The prime, the shelf life of a Mexican Style fighter, is usually not as long.”

Eye of the beholder

In the face of schedule shifts made necessary by the COVID-19 pandemic, boxing’s main calendar dates continue to center around the weekends nearest to May 5 and Sept. 16 — the commemoration of Mexico’s victory over French forces in the Battle of Puebla and Mexican Independence Day, respectively. It’s no coincidence that boxing’s biggest events take place around days relevant to fans of Mexican heritage and are often headlined accordingly.

To that point, using the term Mexican Style to refer to a boxer or in the context of a fight itself evokes notions of entertainment, excitement, aggressive ferocity and the anticipation of witnessing something epic in the ring.

Alvarez knows there will be those who disagree with his take and continue to push the almost romantic, Rocky-esque ideal of a warrior who battles his way to victory not only by outpunching, but by outlasting as well.

“I get criticized anyway,” Alvarez said. “But I do represent Mexico.”